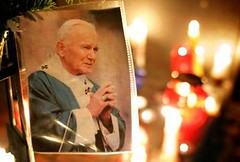

There have been lots of wonderful things said about Pope John Paul II in the days since his death. One of the most interesting and apt of them came from Archbishop Rowan Williams, who described John Paul's last days as a "lived sermon."

In the following, we are encouraged not to dwell on "the frailty of his last years" but on the vitality and action of his early pontificate. I think this is wrong. I think JP2's most powerful witness might well be the frailty of his last years, and particularly of his last days. Of course, we ought not to forget the vitality and action of his early pontificate, but the way he died spoke beautifully of the "culture of life" and was a moving witness to our Lord's passion and death. John Paul in his final days was like a sheep, which before its shearers is silent... quite literally silent, as John Paul apparently had great difficulty speaking as he died.

-------------

Pope John Paul II: His legacy for the church, and the world

John I. Jenkins and John Cavadini

The Boston Globe

Monday, April 4, 2005

NOTRE DAME, Indiana

Among the inspirations of the life of Pope John Paul II was his frequent

reference to the "civilization of love." It was an ideal that sparked the

imagination. Yet it was also a concept consistent with the example of his life

in a culture that is awash at times in cynicism, uncertainty and materialism.

He showed us how to live a life grounded in prayer, but also in reconciliation.

His outreach to the Jewish people, for example, was remarkable at a time in

history when ethnic divisions sometimes threatened the world on a broad level.

He spoke of a special relationship between the Jews and the Church and insisted

that the Old Covenant had never been revoked. His words put forth possibilities

for theologians that are yet to be fully explored.

In one special moment, the pope told an audience of Jews that he regarded them

as "our brothers and sisters in the Lord." Surely this was part of his vision

of a civilization of love.

And in a time when society seems to have lost its ear for the ideals of

procreation and their intrinsic connection to married love, the pope spoke of

the "nuptial meaning of the body" and upheld the values of Pope Paul VI's

controversial encyclical, "Humanae Vitae."

He worked to put the encyclical in a larger context. In his civilization of

love, the procreative ethic and an ethic of seamless love would reject the

negativity of abortion and the refusal of societies to guarantee the education

and health of all their children.

These were not popular views in parts of Western civilization, yet even critics

admired his fortitude and his recognition of heroic possibility in the

aspirations of humanity.

In a self-centered culture, this pope bore witness to service, to personal

sacrifice and the humanizing values rooted in love.

For some, the lives of the saints might seem old-fashioned and certainly a

private domain of the church. But in the pope's civilization of love they were

sources for healing cultures, because they represented the greatness of human

possibility. He once spoke of the way in which Catholic and non-Catholic

Christians died together in Uganda, referring to the "ecumenism of the saints

and of the martyrs," saying that the "communio sanctorum speaks louder than the

things that divide us."

Yes, in the words of the cliché, this pope was a Catholic. But he saw heroic

witness in any people who stood for goodness and hoped for the renewal of

civilization.

So John Paul II could speak in the conviction of the absolute, and hold to

tenets of Catholicism that rankled others, yet avoid triumphalism and

superiority, tendencies that would be blind to the courageous witness of

others. In this, he moved inexorably toward a civilization of love, inspiring

others, particularly young people, to lives of joy and hope.

We should not be focused on the frailty of his last years, but on the incredible

vitality that he brought to his mission during most of his tenure. He went

everywhere, not just centers of Catholicism, whether the American Midwest or a

former Soviet republic or Fidel Castro's Cuba. In his 26-year papacy, he made

more than 104 trips outside Italy, taking in 129 of the world's 191 independent

states. He held talks with more than 1,500 heads of state or government.

His great intellectuality, as expressed in the 14 encyclicals he wrote and 100

other major documents, was an infusion of energy to Catholic intellectual

thought, and he was a powerful influence for all of us at Catholic

universities.

For decades the impact of John Paul II's papacy will be discussed on these

campuses and throughout the world. What remains to be seen is whether his

civilization of love can be realized. It will be food for thought in these

coming days as he is remembered and his image crosses millions of television

screens once again.

The pope did not expect his bold vision to be achieved either quickly or

painlessly, but it begins in the hearts and souls of every one of us. John Paul

II believed in the power of ideals and simple human warmth to inspire a sense of

heroic possibility latent in all of us, Catholic and non-Catholic alike.

He was a gift to Catholics. He was a gift to the world.

(Rev. John I. Jenkins, C.S.C., is president-elect of the University of Notre

Dame. John Cavadini is chair of the theology department at Notre Dame.)

Monday, April 04, 2005

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment