Thursday, August 31, 2006

first things (r.r. reno) ranks graduate programs in theology

This might be an overly bleak assessment. Reno rightly observes that a number of programs have bright lights, but I still think his take is too bleak. He mentions, for example, Gene Outka and Miroslav Volf at Yale as examples of good Christian minds working in the darkness of a pretty thoroughly "post-Christian" faculty. I'm not sure I would agree with that. Yale has made some pretty strong hires lately. I am thinking mainly of John Hare and Denys Turner (in Philosophical Theology and Historical Theology respectively). And there are some pretty bright lights among the junior faculty too.

What do others think of their ranking?

(I was pleased to see Bruce Marshall's "Trinity and Truth" called "as fundamental and revolutionary as Karl Barth's strange and difficult discussion of Anselm...")

man from google joins apple's board

The alliance between Google and Apple may make the prospect of outdueling Microsoft’s empire better than ever.

I am a fan of both Google and (especially) Apple. Read the whole thing here.

Saturday, August 26, 2006

movies i've recently watched

Withnail and I

Withnail and ITerrific: terrifically hilarious, terrifically melancholy. Five stars; five thumbs up. It chronicles the dissipation of a pair of down-and-out young actors who decide what they need is a weekend in the country. There are piquant glimpses, overall, of the pain or despair (or something) that is said to underlie great comedy. And in the meantime we get some of the funniest lines in cinematic history. "These are the sort of windows faces look in at!"

The Phantom of Liberty

Luis Bunuel's penultimate film. Surrealist. Solipsistical. Depressing. Avoid other than for historical reasons. The worldview of this movie reminds me of the last lines of Philip Larkin's poem High Windows:

...And immediately

Rather than words comes the thought of high windows:

The sun-comprehending glass,

And beyond it, the deep blue air, that shows

Nothing, and is nowehere, and is endless.

(Only The Phantom of Liberty lacks the sun-comprehending glass and, thanks be to God, is not endless.)

Lost Boys of Sudan

Lost Boys of SudanA documentary that follows the progress of a group of Dinka Sudanese young men, all orphans, from a refugee camp (in Chad? Kenya? Uganda?) as they make their way to the United States under a program whereby the US government admits 3,000 or so such refugees as immigrants each year. A heart-warming and fascinating story. It makes you angry at the Sudanese government, and frustrated with everyone else (the US, the UN) who sit fairly idly by while yet another African genocide rages right under their noses.

Not particularly memorable for its technical merits, it is nevertheless an engrossing documentary.

Aguirre: the Wrath of God

Aguirre: the Wrath of GodI think I'm more interested in Werner Herzog than I am in his movies. This one is his take on an episode from one of history's more secluded coves: a conquistador from Castile named Lope de Aguirre who set out in 1536 to search for El Dorado, inspird by the tales and treasure of Hernando Pizarro, who had recently returned to Spain from Peru. Aguirre turned into (or maybe already was) a murderous megalomaniac, killing several of his superiors, some of his own men, hundreds if not thousands of natives, and eventually his own daughter. In 1561 he declared himself to be "the wrath of God, the Prince of Freedom, Lord of Tierra Firma and the Provinces of Chile." Shortly afterward he was shot, drawn and quartered.

This movie is typical of Herzog's obsession with obsession. More interesting than the film itself (I thought) was the commentary by Herzog in the "extras" section of the Criterion Collection DVD.

Thursday, August 24, 2006

letter of metropolitan kirill of smolensk and kalinigrad to bishops duncan of pittsburgh, salmon of sc, and schofield of san joaquin

Dear Brother in Christ,

We have learnt from the mass media that you have decided to refrain from recognizing the Presiding Bishop Elect of the Episcopal Church in the USA, Ms. Cathrine Jefferts-Shori. It follows from the released letter you signed that this step was motivated by your refusal to accept the election of a woman to the post of the head of a Church as a gross violation of the old church Tradition. I would like to assure you that I fully share the stand you have taken.

In due time, the Russian Orthodox Church also took not an easy step by ceasing on December 26, 2003, her contacts with the Episcopal Church in the USA because of the ‘consecration’ of Gene Robinson, an open homosexual, as bishop. Through this act, the sinful way of life strictly condemned by Holy Scriptures has been supported by church leaders - the fact that defies any reasonable explanation.

It is my profound conviction that secular liberal political and philosophical ideas, however we may treat them, cannot and must not adjust the Apostolic Tradition and the understanding of New Testament texts guarded by this Tradition. Any attempt to adjust Christian morality and especially the church order to the political tastes of an external environment is dangerous as it threatens with a loss of Christian identity. There must be no fear in the efforts to keep faithful to Christ. Indeed, the Gospel calls us to take the narrow path that many believed to be impossible even during the earthly life of the Saviour: “When the disciples heard this they were greatly astonished, saying, ‘Who then can be saved?’” The example of the Russian Orthodox Church in the Soviet period is a vivid proof that Christians can stay faithful to Christ even in the hardest conditions. Despite the severe persecution and pressure from the Soviet power, our Church did not compromise with the spirit of this world.

We continue to follow the situation in the Episcopal Church in the USA because we have always cherished good relations with her faithful. Dialogue between our two Churches was established over one hundred years ago, St. Tikhon the Patriarch of All Russian being one of its initiators. Since that time, our relations have been marked by sincerity, warmth, willingness to cooperate and mutual interest. Now we, regrettably, have been actually deprived of this rich heritage. However, as the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church stressed in its decision to break relations with the Episcopal Church in the USA, we are open to ‘contacts and cooperation with those American Episcopalians who remain faithful to the gospel’s moral teaching’.

In this connection, I would like to inform you that the Russian Orthodox Church supports your act and expresses willingness to restore relations with your diocese. Using this opportunity, I wish you good health, God’s help in your work, peace and prosperity.

With love in the Lord,

Kirill,

Metropolitan of Smolensk and Kaliningrad,

Chairman Department for External Church Relations

Moscow Patriarchate

Interesting but relatively predictable. ECUSA is definitely maneuvering itself well outside the mainstream of catholic Christianity. Read more here and here .

Wednesday, August 23, 2006

robert wokler

Wokler was the most sympathetic and delightful of friends, the most sparkling, amusing and ebullient of conversationalists; he was also an acutely sensitive and deeply private man - Diderot and Rousseau rolled into one. The companionship and support of American friends he met late in life was an unexpected blessing and, with the affection of older friends and the devotion of his family, a comfort in his last years, which were overshadowed by illness.

Though much of his work was shaped by the times, Wokler's own values, tastes and manners were those of an earlier, more civilised and graceful world than that which he inhabited, and in many ways deplored - and to which his example stood as a dignified, restrained, but determined rebuke.

It was a privilege to be one of those American friends Robert met late in life and whose companionship and support were a blessing to him. I hope that is so. I know its true of MD. Anyway, read the whole thing here. I do miss Robert.

an interview with the archbishop of canterbury

Q: What will happen to the six or more dioceses in America that have asked for alternative primatial oversight?

++Rowan: "I don't know yet. We are working intensively on what this might mean. I don't want to make up church law on the back of an envelope, because in fact it's a very complicated situation.''

Q: It would constitute a split in the American church.

++Rowan: "Indeed, and quite a serious one. And I have great concern for the vast majority of Episcopal Christians in the US who don't wish to move away from the Communion at all, but who don't particularly want to join a separatist part of their Church either. I want to give them time to find what the best way is.''

Q: But these dioceses and the group around them won't hold out in ECUSA for too long.

++Rowan: ''No, and it is perhaps a rather larger group than some have presented it as being. I know too that if Canterbury doesn't help, there will be other provinces that are very ready to help. And I don't especially want to see the Anglican Church becoming like the Orthodox Church, where in some American cities you see the Greek Orthodox Church, the Russian Orthodox Church and the Romanian Orthodox Church. I don't want to see in the cities of America the American Anglican Church, the Nigerian Anglican Church, the Egyptian Anglican Church and the English Anglican Church in the same street.''

Monday, August 21, 2006

so anyway....

Well, MM got the right answer. KingFriend circled around it, then went off in other (helpful) directions. The rest of you just looked on from a half-interested distance. Here's what MM said that I am callign "correct" --

"The probem is perhaps a Protestant refusal to recognize reality as ontologically located in physical substance."

Here's how I would have put it: matter matters. And now that I think of it, maybe it isn't an essentially protestant problem, though it tends to be. Especially among unreflective American evangelicals. But rather than put it in the terms of protestant denials (or "refusals" in MM's terms), maybe we can avoid controversy by putting it in terms of catholic affirmations. Existence in this world is essentially material. We are material beings, embodied souls, etc. And this state of affairs is "good" according to God in Genesis.

Concomitantly, God's self-revelation is always mediated by materiality. He always presents himself to us, in this world, materially -- whether in the flesh of the man Jesus, or in the words of Scripture, or in the Eucharistic Host, or whatever. Even visions, "senses," dreams, intuitions, and what not are presented to you through the functioning of your brain. Which is to say that in this life, your consciousness and psychology is wrapped up in the materiality of the firing of synapses and so forth, in other words, your psychology is packaged in neurobiological realities. (And note I am not saying that consciousness is reducible to neurobilogoical realities, but just that the latter are necessary for the obtaining of the former in this order of existence, which God has caused to be, and which he has called "good.").

It is in this material state of affairs that humans relate to one another. And one of the realities of this necessary physicality is the God-ordained materiality of gender. In short, I agree with Barth. Gender is necessary for humans in this order of existence. And this order of existence is the only one that pertains to us at the moment.

Also note: yes, our understanding of things theological is informed by our eschatological orientation; but pace Scotist, I don't see anything in Scripture or tradition that indicates that our eschatological existence won't be gendered. Apparently we will be neither married nor given in marriage, but that does not mean that we will have transcended our gender particularity, which seems to be wrapped up in our incarnatedness, our physicality. And because one of the main events of the eschaton is the resurrection of the body, it seems to me that our understanding of the eschaton ought itself to be informed by the truths of Genesis.

But anyway, congratulations to MM for winning. And to KF for playing. But since the game was really "read Father WB's mind," the deck was stacked.

Sunday, August 20, 2006

prattle and inanities, &c

What have I done today? A long nap this afternoon. Then sushi for dinner. Tonight has been given to reading and listening to music. I was interested to learn that my favorite rock and roller, Will Oldham (pictured above), aka Bonnie "Prince" Billy, is coming out with a new album in September. Hoozah. A friend sent me a song preview. Here it is.

And, urged on by the conflict betwixt Israel and Hezbollah, I read a story about a 19th century Maronite Saint, St. Charbel Makhlouf.

Friday, August 18, 2006

bishop lee has lost his marbles

Bishop Lee maintains that the recent US General Convention “followed very seriously” the Windsor report, especially its prescription about reconsidering consecration of priests in gay relationships. It has been suggested that ECUSA be demoted to “associate” status in the Anglican Communion, but Bishop Lee felt this would be an extreme reaction.

Bishop Lee maintains that the recent US General Convention “followed very seriously” the Windsor report, especially its prescription about reconsidering consecration of priests in gay relationships. It has been suggested that ECUSA be demoted to “associate” status in the Anglican Communion, but Bishop Lee felt this would be an extreme reaction. “The Episcopal Church took a significant step at General Convention,” even though conservative groups had since denigrated it. “I would be astonished if Archbishop Williams recognises any of these groups as a successor to the Episcopal Church, though I suppose he might recognise them as supplemental.”

But Bishop Lee still hopes that it won’t come to that. “We’re a small Church, and that means that friendship - ‘bonds of affection’, to use Windsor’s phrase - might be our salvation. I think this is where our hope for the future lies, as people realise that we have more things in common than divide us.”

Good grief! Read more here, or the whole thing here. But he's right about one thing: lawsuits would be unbiblical. But then again, so is practicing homosexuality. But two wrongs don't make a right. If legal wrangling commences in earnest within ECUSA, that will be a very serious scandle indeed. And I really hope people would abandon their claims on property before they would initiate a lawsuit, out of obedience to 1 Corinthians 6, which is at least as explicit about lawsuits as St. Paul is elsewhere about the practice of homosexuality. The meat of it: "To have lawsuits at all with one another is defeat for you. Why not rather suffer wrong? Why not rather be defrauded?"On a completely unrelated and somewhat superficial note, I do love the traditional Anglican bishop's choir outfit: the cassock, rochet, chimere, and scarf, which Bp. Lee is modelling to good effect above, though I'm not sure what's up with his collar. I hope that when we are eventually reunited with Peter, these vestments will be retained.

Monday, August 14, 2006

Sermon on the Eucharist, part I

“When the cat’s away, the mice will play.” As you know, our Rector is away on vacation, so I thought I might take the opportunity to do something which is rather infrequently done in Episcopal churches – no, we’re not going to show movies in lieu of Morning Prayer – I’d like to present to you, this week and next, a two-part series of sermons on the Eucharist. The idea is not mine own, I must confess, but seems to be suggested by the gospel readings for this week and next. We’re reading in the gospel of John, the section, as you heard today, where Jesus proclaims Himself to be the Bread of Life, come down from Heaven, and given for the life of the world. I’ve divided these sermons based on the readings themselves: today’s will have to do with the meaning and effects of the Eucharist upon our lives of faith, and next week’s will have to do with the ambitious subject of the miraculous change that takes place in the elements, including the subject of transubstantiation.

By way of disclaimer, one thing that I would like to mention now is that neither of these sermons constitutes an argument for the abolition of our parish’s tradition of Morning Prayer on alternating Sundays or a change in our liturgical style. I love our services of Morning Prayer and neither the rector nor I intend to see them disappear. My intention in these sermons is not to urge change, but to help us appreciate more deeply the practices we already do.

Another thing that needs to be mentioned at the outset is that these sermons will not be systematic or comprehensive. They will probably raise questions that they won’t answer or can’t answer in the short time we have together on Sunday morning.. That’s ok – we encourage questions. They set us to thinking about God, and that’s always worthwhile. I have always enjoyed the feedback this congregation gives, and if you’d like to talk more about the Eucharist with me or with any of your clergy, please know that you’ll be welcome.

Let’s turn our attention now toward today’s Gospel reading. This exchange takes place in the city of Capernaum on the shores of the Sea of Galilee in northern Palestine. At this point in the narrative, Jesus has, within the last 24 hours, fed more than 5,000 people from five loaves and two fishes; walked on the water across the Sea in the middle of the night in an attempt to escape the crowd unnoticed; and calmed the wind and waves and fears of his disciples. He’s been tracked down by the hungry crowd, and they’ve badgered him with requests for more miraculous food production, missing the point that it’s not earthly food that Jesus offers, but spiritual food; in fact, it is himself that he offers: “I myself am the bread of life!” he exclaims in exasperation.

This is where we pick it up today. As Jesus is trying to help the crowds wrap their heads around this idea of himself as spiritual food, he emphasize three things that are important for us as we think about the Eucharist. He talks about Access to the bread of life its Effects upon our souls, and the promise of Resurrection. The key to Access here is in verse 44: “No one is able to come unto me unless the Father who sent me draw him.” The interesting word here is ‘draw’. This is not a gentle word. It’s the word used for ‘drawing’ a sword from its sheath, for seizing somebody and dragging them into court for judgment, or outside the city for stoning. To be dragged kicking and screaming is not too far off the mark here. It’s a violent word, a stark word, a word that brooks no objection, that won’t take ‘No!’ for an answer.

Does Jesus mean we should be violent people, kidnapping others like terrorists in black ski-masks and dragging them to our Eucharists? As effective as that tactic might be for increasing our average Sunday attendance, no, I don’t think that’s what Jesus has in mind here. Rather, he’s describing the grace of God in these violent terms. He’s saying that God draws us to Jesus, the Bread of Life, by an irresistible call of grace that amounts to spiritual violence. It is God’s call to us, and His grace in getting us to this table, that brooks no opposition, overcoming all obstacles in our souls and lives that tend to keep us from responding to the call. This is why Jesus can say in this passage that no one who comes to him will by any means be cast away – he’s been working hard to get us to this table – remember the parable of the shepherd who leaves the 99 sheep to search for the one who was lost – and once he’s found us and brought us here, there’s no way he will ever shoo us away.

What does this mean for the Eucharist? It means, primarily, that access to this table is only by grace. No one can come here unless the Father draws them – and He does draw them; He draws us! It’s only because of the Good Shepherd’s hard work that any of us lost lambs can be here at all. This should, first and foremost, cause us to approach the feast with profound gratitude. But it should also cause us to approach with humility, because this access can’t be earned. It’s not a right or an entitlement, a membership to be bought with money or good deeds or by association. When we walk up these stairs, we approach the Savior who gave his life to clear the path so that nothing would stand in our way. When we cross the floor of the choir, we come near to the God who won’t let our sins or anyone else’s keep us out. When we kneel at this rail, we embrace the God whose arms have been open to us from the very beginning, and who will never let go. That’s what it means when Jesus says, “no one can come to me unless the Father draws him” – He’s a God who won’t let go of you for any reason or at any time in your life’s journey. He’s a God who won’t let go.

That’s an amazing truth. It means we’re all in process of being brought before God’s throne – dragged, really – not so that He can judge us and punish all our wrongdoing, but so that He can insist on forgiving us. Imagine if you lived in a totalitarian state, such as the Soviet Union used to be, and you were known for resisting the ruling government. Suddenly, as you sit in your home, the secret police break in your door and haul you away to an unmarked van. They drive you to the home of the totalitarian ruler, hustle you into a throne room, and pull you across the floor to the throne of the very ruler you’ve spent your life resisting. But as you look up, you see that this ruler is your own father, your own mother; and the ruler’s first reaction is not a stern “off with his head!” but to suddenly drop everything he’s doing and come running to you, embracing you in tears and insisting that all is forgiven and that he’s missed you so much. That’s the picture that Jesus is drawing for us here. We’re all in-process of being dragged to God’s throne, as it were; in-process of meeting our Maker face to face. The Eucharist is itself the means and fulfillment of this process. In it we respond to the powerful call of God, and when we come, we meet our Maker, who insists that nothing stand in the way of full reconciliation and peace between Him and us.

There is a growing movement in the Episcopal Church for Open Communion, which means removing the one restriction we do place on access to the Eucharist – Baptism. The argument for Open Communion is that Christ has removed the obstacles here, so everyone is called, everyone is welcome to come to the table; it’s His table, not ours, and we have no right to turn anyone away. This radical openness is, I must admit, an attractive prospect, but it’s important to note that the Church already has a radically open sacrament. We already have a sacrament from which we never, ever, turn anyone away for any reason – it’s Baptism. Baptism is our radically open sacrament. Everyone is welcome – there’s no obstacle to baptism, if you want to be baptized and you’re willing to profess belief in the Gospel. Baptism is our radically open door, and it leads to the Eucharist. We never close the door to anyone, but we do insist that you go through that door and no other to get to this altar. That’s the only way, really, to take God’s powerful, even violent grace seriously. Baptism, you see, is the sacrament of Grace. It’s the way we acknowledge that God is calling us and the way that we respond, starting our journey toward Christ. That’s why we offer the Eucharist to everyone who has been baptized – everyone who is in the process.

That’s why Jesus goes on to say in verse 45: “Each one who hears the Father’s call and responds arrives at me.” The interesting word here is ‘responds’ – the word in Greek denotes increasing in both mental knowledge AND the knowledge gained by experience; it also means developing habits that support the knowledge you’ve gained. In short, this single word is a fine description for what it means to be a disciple. It’s a lifelong learning process, a commitment to a spiritual journey toward God that consists of increasing in knowledge and practical Christian living. This is what it means to be ‘dragged’ to God, as we discussed above. Each of us here today has heard the call of the Father, so each of us has begun our spiritual journey of mind and practicality, of heart and hand, led onward by the God who won’t let go. Jesus is telling us that as we progress along this journey, we eat the bread of heaven and learn the better to believe in Him. The Eucharist’s Effect upon our spiritual journey is unique, and we can’t find it anywhere else but at Christ’s table. Each Eucharist gives us a little push along the way. Not only are we called ‘dragged’ to the table, but once here we’re given a boost, like a child that is called in to supper but who is too small to reach the table himself, so he’s given a phone book or a booster seat to sit on, so he can reach the table. So it is with us – we’re called in to supper by the God who won’t let go, and not even our own human weaknesses and inadequacies are allowed to keep us from the feast. The Eucharist gives us a booster seat in practical Christian living. It helps us do what we are too weak in ourselves to do. It helps us find not only the knowledge of God but also practical, every-day ways to be disciples, to live out the love of our God who won’t let go. This is the Effect of the Eucharist on our spiritual journeys in the present.

But in this passage Jesus doesn’t speak only about the present. He mentions no fewer than five times that He will raise us up at the last day, or give us eternal life, or bring us to the goal of our journey. Our Eucharistic prayer emphasizes this future effect of the Eucharist, telling us over and over again that this Body and Blood are the pledge of our inheritance. The Eucharist is a foretaste of what is coming for us in the future. This Body and Blood of Christ is the guarantee that God will never let you go. It is the will of God, Jesus says in today’s reading, not to lose any one that he’s been given, but to raise them up at the last day.

The Eucharist is God’s given word that He will include us in the resurrection, that because Jesus’ body was raised from death and made perfect, so also our bodies will be raised from death and made perfect. The God who won’t let go, who pulls and pushes us along the journey, wants all of you – your soul and body; and saves all of you, both soul and body; and gives eternal life to all of you, soul and body. The Eucharist is that process of salvation.

Through the Eucharist, we approach the God who calls us and who won’t let go of us on our journey toward Him. Through the Eucharist, we receive help to grow toward Christian perfection, to know and practically to live out the love of God. Through the Eucharist, we have God’s guarantee of salvation and resurrection in the last day. This is an incredible gift. There’s nothing like it in the whole world. This is why, in our worship, we treat it with reverence. We bow toward the altar upon which this miracle gift comes to us. We approach it through prayer and praise and gratefulness, and we precede it with confession of our sins and the assurance, in absolution, that God forgives us. This is why the Eucharist is so important; we don’t have to do it every week, but we do have to do it. May the God who won’t let go keep us in His love.

AMEN.

from dr. william tighe

Read the rest of Dr. Tighe's comment here (along with the other comments).

It does seem to me that what he is decrying about Anglican

ecclesiology is one of the long-term fruits of two related tendencies:

the basically Erastian nature of the Elizabethan Settlement (1559), in

which the State imposed its will on the Church of England, both in

separating it from Rome and subsequently in imposing upon it a clearly

but moderately Protestant doctrinal stance (the 39 Articles) and

subsequently preventing it from clarifying its confessional stance in

later doctrinal controversies (cf. the failed “Lambeth Articles” of

1595); and, secondly, in consequence of the first (and once the

inability of the Church of England to further clarify its doctrinal

stance ceased to be regarded as regrettable by its leaders, but rather

as a virtue), the “inhabiting” of Anglicanism by three different

theological strains whose presuppositions and orientations were and are

fundamentally at variance with one another, and irreconciliable: the

Evangelical (Protestant, “lowchurch” or whatever; sometimes claiming

the mantle of “Reformed Catholic”), the Catholic (”English Catholic,”

Laudian/Caroline, “highchurch” or, latterly, Anglo-Catholic — all but

the last also asserting claims to the title “Reformed Catholic”) and

the Liberal (evolving [or perhaps devolving] out of the Latitudinarian

or “broadchurch” party, but recruiting adherents from the other two

groups). The advantage that this latter group has always had over the

other two rests on several bases; (1) its claim to provide a synthesis

between the views of the other two groups (one which with the passage

of time, as with any dialectical philosophy, may be constantly receding

into the future, like a mirage), or at least a via media between them,

(2) its ability to represent itself as “moderate” rather than as

“extreme” (this was, of course, possible only so long as all three

parties shared a conventional orthodoxy on basic issues of theology and

Christology, and on morality; with the passage of such a conventional

orthodoxy, the liberals can be seen for the true radicals) and (3) its

embracing a sort of “neo-erastianism” as fundamental to its identity.

The “old Erastianism” held that the monarch, or “civil magistrate” had

power over and even within the church: power, especially, to regulate

(1) the internal and sacramental life of the church, and the discipline

that church officials could exercise over the heterodox and the

immoral, and (2) to determine what was basic in the church’s doctrinal

stance and the extent to which it could enforce adherence to it over

members. The “new Erastianism” also looks to, and defers to, an

authority outside the church and its doctrinal tradition or

confessional standards: one might say that it has a tendency to confuse

the Holy Ghost with the “Zeitgeist” or at least only subjective

criteria (whether scholarly or emotional or cultural) for

differentiating between the one or the other (i.e., if Jesus is another

Socrates, why isn’t Socrates just as good as Jesus; and if this is true

of Socrates, why not Nietzsche? Or if homosexual genital partners can

have their “monogamous” relations “blessed,” why not polygamous or

polyandric relationships?)

The result of this, as we see today in ECUSA, is that Episcopalians

have ended up in a situation analogous to that which the once-Calvinist

(but “empirically Calvinist”, that is, without any binding confession

of doctrine) “Standing Order” of Massachusetts Congregationalism ended

up by about 1820 — when unitarians and trinitarians contended in

umbrageous struggle in the same institution, a struggle ended only by

disestablishment in 1832, and the ability of each Massachusetts parish

to choose its affiliation by the vote of all members. Of course, in

1820 rationalism and moralism formed the predominant cultural outlook

in New England, and consequently the argument between the two parties

revolved for the most part around rational philosophy and biblical

exegesis. Today, it has devolved (for the most part) into a subjective

free-for-all. But when a commentator here on Titusonenine can write,

for example, that Jesus was “mistaken” on marriage and divorce, and at

the same time regard himself as a Christian and an Anglican, it is

pretty clear that ECUSA has hit the same rock bottom as the Unitarians

(and it’s hard to see that the Canadians or the English are too far

behind). And worse even — for whereas the Unitarians continued for 75+

years to regard the Lord Jesus as in some sense “divine” and certainly

as “savior,” these Liberal Anglicans would seem in practice to reduce

him to the status of a Socrates, a Plato or a Confucius, a figure whom

one finds “inspiring” in some sense, but in no meaningful sense

“divine.”

My late friend Fr. Joseph M. Elliott (1934-2002), the whole of whose

life from 1959 onwards was spent ministering at St. Paul’s Church in

The Bronx, NY (as seminarian intern, curate, priest-in-charge and

ultimately Rector) — a man whose theological outlook was an eclectic

mixture of Barthianism, Scriptural inerrantism and Catholic

sacramentalism — towards the end of his life once summarized his own

disillusioned evaluation of Anglicanism as “It was good while it

lasted, but it was not good enough to last.” Sadder words were never

spoken; and sadder still if true. Perhaps Dr. Zahl is in the process of

coming to a similar realization.

Sunday, August 13, 2006

things are not as they seem

What is this "other" hope? It may well be the alternative of becoming a Roman Catholic. If your ecclesiology has survived the end of apostolic life in the Episcopal Church, then you may well consider entering the Roman Catholic Church. This is a very live option for all of us, and is even more attractive in relation to the present Pope.

Read the whole thing here. He seems to be down, himself, on the whole notion of "ecclesiology." But we don't have to be. One of the entral messages of the Gospel is that "things are not as they seem." And that goes for the Church, which often seems in its local particularity to be anything but holy, catholic, or apostolic.

This, too, must be at the bottom of the Lutheran / Catholic debate over infused vs. imputed righteousness. Luther must have thought that righteousness can't be our own, because we seem to all eyes to be so unrighteous. But, thanks be to God, things are not as they seem.

Friday, August 11, 2006

you rogues!

Wednesday, August 09, 2006

a theological blog contest! a.k.a. what's wrong with this?

He basically, as far as I can tell, believes that the account of God's creation of man and woman in Genesis does not undergird, or does not primarilly undergird, Christian marriage. This belief of his, of course, is a step in his syllogism concluding with something like "...therefore men may marry men, and women may marry women."

The Scotist takes aim at the following passage from Barth, cited by Dr. Harmon in the original article:

Man never exists as such, but always as the human male or the human female. Hence in humanity, and therefore in fellow-humanity, the decisive, fundamental and typical question, normative for all other relationships, is that of the relationship in this differentiation.The Scotist helpfully observes, pace Barth and Harmon, that not "ALL" relationships are undergirded by gender difference. For example, the relationship between men and angels is presmuably not so undergirded, and neither is that between men and God (who is essentially not-gendered). Here is my question, and maybe someone with a copy of the Church Dogmatics (III.4, p. 117) can answer it: is Barth not talking about all HUMAN relationships being undergirded by the gender differentiation of Genesis? He starts the sentence, after all, "Hence IN HUMANITY, and therefore IN FELLOW-HUMANITY," etc.

That would be a much more sensible construal of Barth. Of course God's transcendence of gender is not governed by God's having created man male and female. Why should it be? And likewise with angels. On the other hand, God's relating to humans IS governed by the facts surrounding him as they are revealed in Scripture. Just so with Angels. And so too are Inter-human relationships governed by the facts surrounding humans, as those facts are revealed in Scripture. Such a fact is that "male and female he created them." Another such fact is "the husband is the head of the wife as Christ is the head of the church, his body, and is himself its Savior" (Ephesians 5.23).

But here is the meat of the Scotist's critique:

If our reading of Genesis is to be normative among Christians, it should start with the revelation of the Person of Christ in Scripture.And skipping down a bit, after a citation from Ephesians 5, we find that

The mysterious eschatological union of Christ and the church is normative for marriage. The Word left the Father to be joined with us, to become one with us, the church. That pattern of action is a model for human marriage...I would have said "That pattern of action is THE model for Christian marriage," but nevermind. It all seems well and good, but if I haven't given it away already, what do YOU think is the theological error here? Or is there an error? I think there is. Hint: I think this error is one of, if not THE most fundamental Protestant error. The error, in fact, separating Protestants from Catholics, and possibly construable as constitutive of Prot / Cath differentiation itself. Another hint: Cf. John 1.

Monday, August 07, 2006

movies i've watched recently

1. I Confess

A Hitchcock movie with Montgomery Clift and Anne Baxter. Top shelf. I recommend it highly. Five stars, etc. Deacon Awesomo was right. Hitchcock at his best. And its all about a priest.

2. Dragonslayer

The kind of uncompromising nonsense that could only have been made in the 80's. It shies away neither from gore, nor nudity. Its replete with stop motion animation, and a facile condescension toward Christianity which sort of rankles. They don't make 'em like that anymore. Thank God. Its certainly no Willow. In fact: four thumbs down.

3. Through a Glass Darkly

Ingmar Bergman again. Matches my mood lately. I think this one is rather more beautiful, and less overbearing, than The Seventh Seal. And Harriet Andersson's performance as Karin is really quite something. An intelligent -- and not altogether hopeless -- take on faith, love, family, narcissism, God, etc. The usual Bergman stuff, what? But, as I said, more beautiful and less overbearing.

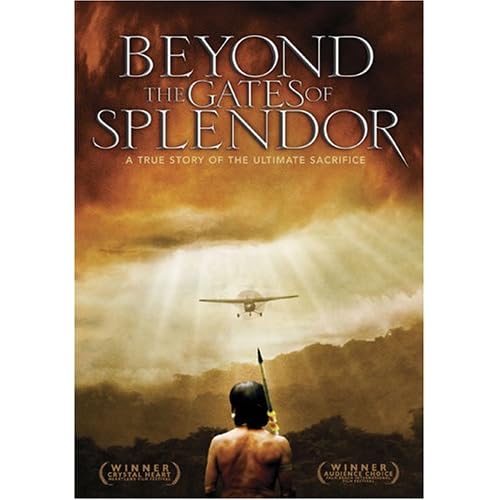

4. Beyond the Gates of Splendor

Amazing. Documentary about five Protestant martyrs who worked among the natives of Ecuador. This movie just might blow your socks off or reduce you to tears. Its a very well-crafted and timely reminder that, contrary to what General Convention may tell you, mission and evangelism are much more than the Millenium Development Goals. Or should be.

Friday, August 04, 2006

my friend, robert wokler

Here (and here) is Robert's obituary from the London Times.

Here (and here) is Robert's obituary from the London Times.Eloquent and hilghly regarded scholar of Rousseau and the Enlightenment

THE LIFE of Robert Wokler embodied the political and intellectual tragedies and controversies of the later 20th century. A Jewish survivor of Nazi-occupied Europe, he was close to the leading intellectual historians of the prewar generation and lived to contest with postmodernism the identity of the Enlightenment and its supposed responsibility for the tragedy of the Holocaust into which he was born.

Born Robert Lucien Wochiler in 1942 in Auch, France, to Polish and Hungarian Jewish refugees, Wokler began his life by saving that of his parents: his infant status gained all three of them entry to Switzerland, enabling them to escape deportation to the death camps where his maternal grandparents had been murdered. Schooling, begun in Paris, was completed in California, where the family settled. A prodigious violinist, Wokler gained a National Merit Scholarship to the University of Chicago to study under Walter Piston, but soon switched to social sciences, graduating in 1964.

He came to Europe for the MSc in the history of political thought at the LSE run by Michael Oakeshott and Maurice Cranston, before moving to Oxford, where his DPhil supervisor was Isaiah Berlin, and his college adviser John Plamenatz. To all of these, and to Ralph Leigh, with whom he later worked at Cambridge on the latter’s magisterial Correspondance Complète de Jean-Jacques Rousseau, he remained close, contributing later to the festschrifts for all three Oxbridge mentors and co-editing Leigh’s. His early career thus gave him a unique exposure to the different anglophone schools in the history of social and political thought and, in the case of the English institutions, a very close connection to the most influential teachers of the age. Early posts followed at Magdalen College, Oxford (1967-71, in modern history), and Reading (1968-71, in politics and French studies). But it was at Manchester (1971-98) that he made his career, successively as lecturer, senior lecturer and then Reader in history of political thought in the university’s government department, which developed, during his time there, a considerable reputation in political theory.

He was always bursting with ideas and projects, and the very range and diversity of his activity precluded the completion of many of them. His loyalty to his teachers consumed much of his considerable energies. He re-edited Plamenatz’s influential three-volume Man and Society in order to replace the contextualising material that had been removed at the original publisher’s insistence, giving a misleading impression of abstraction. At his death he was editing Plamenatz’s unpublished lectures, which had influenced generations of Oxford PPE undergraduates. He was immensely fond, too, of Berlin (of whom he was a brilliant mimic), contributing to his festschrift, The Idea of Freedom (Oxford, 1979), and among his last concerns was to see a study of Berlin’s posthumous Political Ideas in the Romantic Age through the press.

He was among the most articulate and eloquent speakers of his generation, one of the few who retained a focus on extempore speaking as a distinct art. At the closing session of the Netherlands Praemium Erasmium awards conference in 1999 he delivered, with barely a note, an extended account, of immense erudition and insight, of the previous two days’ contributions.

It is an indictment of the university system that a scholar of his calibre never held a chair. He left Manchester in 1998, having already held fellowships at many of the world’s leading research institutes, including in the US, Australia, Sweden and Hungary, and then adopted the role of peripatetic scholar, to which, being increasingly irritated by the conformity and regulation imposed on teaching in UK higher education, he was in many ways well suited. He held short-term posts at Budapest, Exeter, the European University Institute, Florence, and latterly at Yale, where he seemed at last to have found an environment that supported his considerable energies, and where he had recently turned his attention to the political thought of the Ancient world.

But his greatest contribution has been to our understanding of the Enlightenment, particularly the thought of Rousseau, who was the subject of his doctoral thesis, two of his books, and two collections of essays, as well as being the subject of many of his numerous scholarly articles. Allied to, and emerging from, his interest in Rousseau, particularly the latter’s Discours sur l’inégalité, was his work on the origins of anthropology and the social sciences in the increasingly historicised conception of human nature in the 18th century.

His articles on the Enlightenment debate about the relationship between humans and the great apes illuminated not only pre-Darwinian thinking, but also our own presuppositions about such issues. His enthusiasm for the Enlightenment extended, too, to its vigorous defence against many of the cruder construals of it, made in the name of postmodernity. This led to a series of essays that challenged his identity as an essentially historical scholar: Regressing towards Post-Modernity, the Enlightenment, the Nation-State and the Primal Patricide of Modernity, and The Enlightenment Project on the Eve of the Holocaust all address postmodernity’s charge that Enlightenment is the source of modernity’s ills, and its supposed identification of reason with that narrow and ungrounded instrumentality which was claimed to underpin totalitarianism. He defended instead the Enlightenment itself and the way scholars have invoked it as a source of the essentially human and civilising values he embodied in his own career.

He leaves several books, a mass of scholarly articles, and his principal project, the Cambridge History of Eighteenth-Century Political Thought (edited with Mark Goldie), publication of which is imminent.

He did not marry.

Robert Wokler, historian, was born on December 6, 1942. He died of cancer on July 30, 2006, aged 63.

Tuesday, August 01, 2006

but thou hast in love to my soul delivered it from the pit of corruption: for thou hast cast all my sins behind thy back

Thanks be to God. May their souls, and the souls of all the faithful, through the mercy of God, rest in peace.