**Updated**

[See also MM's pertinent take here. And WB, perhaps I have answered or echoed your trenchant anaylsis in the comments. Thanks both.]

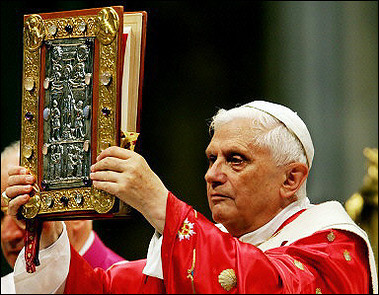

This article was the lead headline in the print edition of the New York Times today. In light of Pope Benedict's upcoming trip to Brazil, it considers the state of liberation theology in Latin America today (still going fairly strong, apparently). The article discusses Benedict's crackdown on LT's heretical tendencies when he was still Cardinal Ratzinger and the Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. The problem with LT combines elements of Marxist theory and Christian belief to suggest that Jesus was a sort of Che Guevara of the first millennium. The NYT suggests that the pope's attitudes towards LT have "softened," but this is I think a their misreading. What the pope may have acknowledged is that, in so far as LT tends the needs of the poor and downtrodden, it does what correspond to Christ's commandments: to feed the hungry and clothe the naked. That does not, however, translate into Christianity finding its fullest expression in the Marxist state.

Benedict took up the issues of LT, Marxism, and modern thought in general in his Introduction to Christianity (see the updated preface and introduction), which I have at last taken off my bookshelf and been reading. His point is to recall the uniqueness of the Christian worldview and its central faith in Christ Jesus. When it is admixed with foreign ideologies, its salvific power is seriously undermined. The NYT, like all organs of modern thought, does not see it this way. It persists in believing that there are a plurality of equally legitimate beliefs in the world, and this extends to religion. We should not speak of theology, but theologies, not orthodoxy but orthodoxies. This of course is just an updated, less vigorous, and therefore less satisfying form of Marxism. This of course is nonsense from the inside of the Christian worldview. If the way is not narrow that leads to eternal life, it is not the Way.

Benedict laments in the Intro. that Christianity missed a key opportunity in the last century to engage the world by virgorously countering the corrosive philosophies of Marxist materialism. In 1968 and again in 1989, when the world groaned under the yoke of oppression, the Church failed to make its voice heard, to proclaim the Gospel in the face of social, economic, and cultural dissolution. The instruction given by the CDF in 1984 speaks of the "impatience" of those eager for social justice (a much maligned term in the church these days) who have turned to Marxism in order to pressure society into effecting the Kingdom of Heaven. The problem is those ground-of-being assumptions that Marxism makes about the world differ wildly from those of Christianity. Marxism rests its claims on science, assuming that "science" somehow embodies an objective view of the world and of man and that if human relations can be goverened objectively, then they can be harmonized. The failure of Marxism to achieve such a goal rightly points out the failure of a scientific-materialist world view, that matter cannot provide an objective view of matter. It is the recognition that science has been coming to itself going on a century now. But does this mean we should give up on objectivity? The pluralism latent in the NYT article suggests that we ought to, but as I love to make a point of, such an attitude itself appeals implicitly to an objective order: the objectivity of no-objectivity. But this is mere incoherence. Christianity, on the other hand, recognizes that true objectivity can only be found outside of this world, the world must be considered as an object, and that perspective can only come from the Divine.

It is increasinlgy clear to me, as it was to Benedict forty years ago (the Intro was first published in 1969), that Christianity today has a golden opportunity. From an intellectual standpoint, it's never been easier to justify our faith to the world. As global politics continually show, people desperately want coherence, order, objectivity, and hope, all of which can be found in the Church, and which can only be found in the unique expression of that faith which is the unadulterated belief entrusted to the apostles by Christ. Christianity has not survived or flourished because it rests on universal myths which are reluctantly giving way to the objectivity of science, but because it in itself offers for the first time an objective perspective on the world that resonates with our experience of the world.* When we forget that, we get caught on the same slippery slope that courses straight into the abyss of nihilism.

________

*This by the way is the perspective offered by René Girard in Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World, but there is not room to expound on that here.

[See also MM's pertinent take here. And WB, perhaps I have answered or echoed your trenchant anaylsis in the comments. Thanks both.]

This article was the lead headline in the print edition of the New York Times today. In light of Pope Benedict's upcoming trip to Brazil, it considers the state of liberation theology in Latin America today (still going fairly strong, apparently). The article discusses Benedict's crackdown on LT's heretical tendencies when he was still Cardinal Ratzinger and the Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. The problem with LT combines elements of Marxist theory and Christian belief to suggest that Jesus was a sort of Che Guevara of the first millennium. The NYT suggests that the pope's attitudes towards LT have "softened," but this is I think a their misreading. What the pope may have acknowledged is that, in so far as LT tends the needs of the poor and downtrodden, it does what correspond to Christ's commandments: to feed the hungry and clothe the naked. That does not, however, translate into Christianity finding its fullest expression in the Marxist state.

Benedict took up the issues of LT, Marxism, and modern thought in general in his Introduction to Christianity (see the updated preface and introduction), which I have at last taken off my bookshelf and been reading. His point is to recall the uniqueness of the Christian worldview and its central faith in Christ Jesus. When it is admixed with foreign ideologies, its salvific power is seriously undermined. The NYT, like all organs of modern thought, does not see it this way. It persists in believing that there are a plurality of equally legitimate beliefs in the world, and this extends to religion. We should not speak of theology, but theologies, not orthodoxy but orthodoxies. This of course is just an updated, less vigorous, and therefore less satisfying form of Marxism. This of course is nonsense from the inside of the Christian worldview. If the way is not narrow that leads to eternal life, it is not the Way.

Benedict laments in the Intro. that Christianity missed a key opportunity in the last century to engage the world by virgorously countering the corrosive philosophies of Marxist materialism. In 1968 and again in 1989, when the world groaned under the yoke of oppression, the Church failed to make its voice heard, to proclaim the Gospel in the face of social, economic, and cultural dissolution. The instruction given by the CDF in 1984 speaks of the "impatience" of those eager for social justice (a much maligned term in the church these days) who have turned to Marxism in order to pressure society into effecting the Kingdom of Heaven. The problem is those ground-of-being assumptions that Marxism makes about the world differ wildly from those of Christianity. Marxism rests its claims on science, assuming that "science" somehow embodies an objective view of the world and of man and that if human relations can be goverened objectively, then they can be harmonized. The failure of Marxism to achieve such a goal rightly points out the failure of a scientific-materialist world view, that matter cannot provide an objective view of matter. It is the recognition that science has been coming to itself going on a century now. But does this mean we should give up on objectivity? The pluralism latent in the NYT article suggests that we ought to, but as I love to make a point of, such an attitude itself appeals implicitly to an objective order: the objectivity of no-objectivity. But this is mere incoherence. Christianity, on the other hand, recognizes that true objectivity can only be found outside of this world, the world must be considered as an object, and that perspective can only come from the Divine.

It is increasinlgy clear to me, as it was to Benedict forty years ago (the Intro was first published in 1969), that Christianity today has a golden opportunity. From an intellectual standpoint, it's never been easier to justify our faith to the world. As global politics continually show, people desperately want coherence, order, objectivity, and hope, all of which can be found in the Church, and which can only be found in the unique expression of that faith which is the unadulterated belief entrusted to the apostles by Christ. Christianity has not survived or flourished because it rests on universal myths which are reluctantly giving way to the objectivity of science, but because it in itself offers for the first time an objective perspective on the world that resonates with our experience of the world.* When we forget that, we get caught on the same slippery slope that courses straight into the abyss of nihilism.

________

*This by the way is the perspective offered by René Girard in Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World, but there is not room to expound on that here.