In a gesture of shameless self-promotion, here is the sermon I preached yesterday:

“For the message about the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God.”

In the name of the + Father…

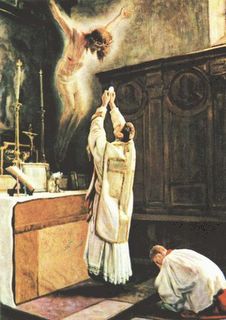

For many, the chief intellectual hurdle in the Christian project is seeing or experiencing the victory of the cross. I mean it is telling, and a bit odd, that the most recognizable symbol of Christianity is the cross… not a stone rolled away or a dove descending or that little fish that goes on your car’s bumper. The most recognizably Christian symbol, the world over, down through the centuries, is an instrument of torture and death, a cross. How is it that Christians have, since the beginning, found their identity as a body in that instrument of suffering and death? It is this question to which St. Paul addresses himself in the first chapter of 1 Corinthians.

As many of you know, Jacques Derrida was a French intellectual famous for inventing or discovering Deconstruction, a technique by which literally everything is called into question and turned on its head. During the evening of Friday, October the 8th 2004, in a move of uncharacteristic certitude and clarity, Derrida died. A friend of mine broke the news to me in an email the following day, concluding “I suppose if he died in Christ, even his death can be called into question.”

In one of Derrida’s books, “Given Time: Counterfeit Money,” Derrida sets about deconstructing, picking apart intellectually, the activity of gift-giving, concluding in the end that it is impossible to give a gift. What Derrida means, I think, in saying that it is impossible to give a gift is that gifts are by definition free. They are given, plain and simple. In order for a gift to be a gift, it has to be free, dissociated from reciprocity. For if you give a gift to someone and they give something back, in return, the gift has become an exchange, and insofar as it is an exchange, it is not a gift. But Derrida notes that every time we give each other gifts, we do get something back, even if its just the satisfaction of having given the gift. For Derrida, then, the gift is the impossible.

If Derrida is right, we Christians are in a lot of trouble… for our whole way of seeing the world, all of our activities, our presence here, our coming together to worship, our eating the bread and drinking the cup, our very life, is based on the assumption that we have received a gift. Recall the words of the angel to the shepherds keeping watch over their flocks by night: “for to you is born this day in the city of David a savior which is Christ the Lord” (Luke 2.11). Its not merely that a savior is born, but rather that to you is he born, echoing the words of the prophet Isaiah: “for unto us a child is born, unto us a Son is given” (Isaiah 9.6). And for Christians it is practically impossible to see the child lying in the manger without the assurance that this child, thirty-three years later, will be given with awful finality, pierced and broken and bloody, stretched out on the hard wood of the cross.

Derrida was right, in a way, because he spoke from the finite vantage point of time and space, he spoke on the world’s terms of fairness, of measured reciprocity, of market transactions, of what he called tit-for-tat giving and counter-giving. For us it is impossible to give pure gifts, free of the taint of self-satisfaction at the very awareness that we have given a gift. But as Jesus himself said, “with men it is impossible, but with God all things are possible” (Matthew 19.26, Mark 10.27). Derrida spoke with the wisdom and discernment of our age, an age of reason and reasonableness, an age purged of the vestiges of myth, in which miracles are either denied or explained away. But St. Paul here in 1 Corinthians, quoting the prophet Isaiah (Isaiah 29.14) reminds us that God, in embracing us, has disavowed our pretenses and our social constructions: “I will destroy the wisdom of the wise, and the cleverness of the clever I will thwart” (1 Corinthians 1.19).

The cross is for all of us the destruction of human wisdom and cleverness. It is our life through his death. Speaking about God the Father, St. Paul says “He is the source of your life in Christ Jesus, who became for us wisdom from God, and righteousness and sanctification and redemption” (1 Corinthians 1.30). Wisdom from God. It is the whole scheme of human wisdom and cleverness that produces and holds up the gadflies of religion, men like Jacques Derrida, telling the world of the complete impossibility of genuine gift giving. In our day it is Derrida, but the world has always had its class of wise and clever men, oracles, sophists and cynics. And they do, in a sense, have a meet and fitting social function. They are there to be thorns in our flesh, pointing to the futility of our efforts, that the wellspring of our generosity and humanism is vanity and a chasing after wind.

But once, in the middle of all the rhetoric, something quiet and unexpected happened. A child was born, a Son was given. You can imagine how Hell and the powers of darkness must have roared. They (and we) had been taught to expect something quite different. The solution to our problems we would expect to come charging into town riding an Abrams Tank or administering a social program.

Instead we get something quite different. We get a helpless child. And the helpless child grows into a man. And the man goes around Galilee healing the sick and teaching freedom to the captives, it is true, but in the middle of all of his good and useful works and teachings, there is a curious subtext: blessed are those who have nothing to eat, blessed are those who are powerless, blessed are those who have no money, blessed are those who have nothing whatsoever, indeed blessed are those who have everything taken from them: “blessed are you when men revile you and persecute you and utter all kinds of evil against you falsely” (Matthew 5.11). But most curiously of all, right in the middle of this revolutionary and hopeful new ministry, he abandons it. Luke describes Jesus’ face as having become “set towards Jerusalem,” and in Jesus’ own words to his disciples: “Behold, we are going to Jerusalem; and the Son of Man will be delivered to the chief priests and scribes, and they will condemn him to death, and deliver him to the gentiles to be mocked and scourged and crucified” (Matthew 20.17ff).

We are meant to take from this story that Jesus’ teaching and ministry, while unprecedented and wonderful, plays a supporting role to the main event: that Jesus came to give himself to us. And this is what cannot be comprehended on the world’s terms. Derrida is right: we as human creatures are completely incapable of giving pure gifts. The whole Old Testament can be interpreted as a series of stories about God’s demanding a pure gift and Israel’s perpetual inability to give one. So the Son of God comes among us and does the impossible: he gives to us the only pure gift in the history of the cosmos: himself. His own life is poured out for us.

This is the wisdom of God, and it turns our wisdom and cleverness completely upside down. The message we as Christians have been given by God, is far more radical than humanitarianism, it is far more radical than our good and useful ministries of justice and mercy. The source and content of our life is in the death of our crucified and risen Lord, the source of our fullness is in his emptiness on our behalf, the source of our riches is in the poverty he embraced, the source of our power is in his having become our servant. This is what St. Paul calls “a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles” – that “God’s weakness is stronger than human strength” (1 Corinthians 23-24). In the end, I think Derrida could not see it: he concluded, rather hopelessly, that the pure gift is impossible. And the world struggles to see in the Christmas crib, and much more in the insulted face of the Crucified, the power and the glory of God.

And that’s where we, the Church, come in. We have been entrusted with the proclamation of our crucified and risen Lord. That’s what we are doing here. That’s what this Eucharist is. It is the content of our proclamation: Christ has died, Christ is risen, Christ will come again. Christ is given for you and me. And it is our power to go out from this place, in peace, to love and serve the Lord; to go back into our little worlds (the laboratories, libraries, classrooms and social scenes) with their little wisdoms and clevernesses, proclaiming God’s transforming foolishness, in which we are blessed to boast.

Thanks be to God. Amen.